Wide Crosses Among Succulent Plants

Text & Photo: Gordon D. Rowley

Cactus & Co. (Italy) 4(6) 2002

Title page |

Succulents and orchids stand apart from most other flowering plants in the

ease with which wide crosses can be made. A wide cross is a hybrid between

two plants so dissimilar in appearance that one would not expect them to

interbreed. Since classical times it has been recognised that it is rarely

possible to hybridise animals or plants that are not obviously closely

related. A rose will cross with another rose, but not with a peony or a

camellia. But among the succulents we encounter many surprises.

Both succulents and orchids are highly specialised in evolutionary terms,

but it seems that the basic flower structure has diverged less than the

plant body, at least in setting up genetical barriers to outcrossing that

usually accompany (and initiate) speciation. Under favourable conditions in

cultivation, when plants widely separated in the wild are brought together

in one glasshouse, remarkable intermarriages have been engineered. A

selection of them are examined and illustrated here.

There are no obvious rules on why some plants are more promiscuous than

others. Some of the most bizarre couplings unite species classified within

the same genus. A good example of this is Senecio 'Hippogriff (illustrated

in Cactus & Co. 6 (1): 48, 2002) combining S. articulatus and S. rowleyanus.

Here we are more concerned with those that bridge species of separate

genera, such as X Cremnosedum 'Little Gem' (Fig. 1), involving species of

Cremnophila and Sedum. The nothogeneric (hybrid generic) names aid in

pinpointing the ancestry. We call such examples intergeneric hybrids or

bigeners. Where several occur, we may doubt if the two "genera" are really

distinct, especially if the hybrids show some fertility: good pollen or seed

set. A good example is the cactus shown in Fig.2: a long-favoured basket

plant born in England in 1830 and attributed to Aporocactus flagelliformis

(the rat-tail cactus) X Heliocereus speciosus. Today both these genera are

amalgamated under Disocactus (Anderson 2001), so that what was an

intergeneric hybrid is now monogeneric: Disocactus X mallisonii. It has a

measure of self-fertility and sets some viable seed in small fleshy fruits

(Fig. 3). Most wide crosses, like the mule, are sterile. However,

intercrossability and intersterility are only one factor in determining the

distinctness of genera, and often it is more desirable to retain a pair of

genera as distinct despite the existence of crosses between them. In a

survey of succulent bigeners in 1982, the most numerous were classed under X

Pachyveria (Pachyphytum X Echeveria, 29 cases, Figs.4, 5) and X Gasteraloe

(Gasteria X Aloe, 24 cases, Figs.6, 7). Today there are doubtless more.

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

| | | | | | |

Wide crosses are rare in nature (Fig. 8) because normally barriers have

arisen in the course of evolution. For instance, we find related species

flowering at different times, serviced by different pollinators or

genetically blocked at different stages from accepting alien pollen. In

cultivation it may be possible to overcome such barriers, and merely packing

plants together on a glasshouse staging may result in bizarre seedlings

coming up spontaneously. They can pose quite a problem when one tries to

guess the parentage.

All the largest families of succulents provide examples of wide crosses. It

used to be thought that the Aizoaceae (Mesembryanthemaceae) was an

exception, but this is no longer true. The breeding expertise of Steven

Hammer has resulted in many extraordinary wide crosses, 20 of which have

received nothogeneric names (Hammer 1995; Fig. 9)- In Cactaceae there are no

hybrids known between genera belonging to the different Subfamilies, and

some of the largest and most sharply defined genera of Cactoideae have

resisted efforts to cross their species with outsiders: Mammillaria,

Astrophytum, Ariocarpus, for example. Elsewhere the opposite is true, and

some remarkably dissimilar species have been successfully interbred. Fig. 10

shows Gil Tegelberg standing beside his plant raised by crossing the

red-flowered diurnal epiphyte Disocactus (Heliocereus) speciosus with the

columnar, nocturnal Pilosocereus palmeri. The extraordinary long-tubercled

Leuchtenbergia has been mated with species of Ferocactus and Thelocactus

with surprising results (Fig. 11). Differences in flower size and tube

length may not debar intercrossing, although when making the attempt it is

wise to use the short-tubed cactus as the female parent: its own pollen may

be unable to grow down the long style of the other. The longest flowers, as

in Echinopsis and Epiphyllum, are pollinated by hawk-moths; shorter narrow

tubes favour birds and the shortest funnel-shaped blooms bees. Thus in

nature these are kept apart by pollinator fidelity, but even here mistakes

can sometimes occur. In an analysis of 29 records of naturally occurring

cactus bigeners (Rowley 1994) I found about one third were between plants

adapted for different pollinators: bees, bats, birds or moths.

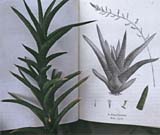

Fig. 12 shows typical flowers of two related genera: Gasteria with hanging,

tubular, red and yellow blooms typical of bird pollination, and Haworthia

with smaller, erect, oblique-limbed whitish flowers favoured by bees. The

hybrid between them (X Gasterhaworthia) has flowers of intermediate

character, but unlikely to suit either pollinator (Fig. 13). Hybrids

involving Haworthia X Aloe are surprisingly few. Fig. 14 shows one example,

as yet unflowered.

Some wide crosses are of curiosity value only. Echinocereus knippelianus X

Sclerocactus (Toumeya) papyracanthus (Fig. 15) sports a diversity of spines

from needle-like to flattened, weirdly disordered tubercles and small,

abortive flowers. A hybrid of Cleistocactus strausii X Echinocereus

(Wilcoxia) poselgeri (Fig. 16) is hardly an improvement on either parent. By

contrast, other wide crosses have great horticultural appeal combined with

hybrid vigour and ease of propagation. Such a one is Pachypodium 'Arid

Lands' (see title photo), a remarkable blend of two totally contrasted South

African species, P. namaquanum and P succulentum. Disocactus X mallisonii

(Fig.2) has already been mentioned; the North American and Mexican

Crassulaceae have spawned many desirable cultivars intermingling genes of

Echeveria, Graptopetalum, Pachyphytum and Sedum (Figs. 1, 4, 5, 17). Many

have arisen spontaneously and we can only guess the pedigrees, but they are

nonetheless worth adding to a collection. Who knows what further novelties

await the pollinator's brush?

REFERENCES

- ANDERSON, E. F. (2001). The Cactus Family. Timber Press, Oregon.

- HAMMER, S.A. (1995). New nothogenera, and a new combination in Mesembryanthema. Cact. Succ. J. (U.S.) 67: 172-173.

- ROWLEY, G.D. (1982). Intergeneric hybrids in succulents. Nat Cact. Succ. J. 37: 2-6, 45-49, 76-80, 119.

- ROWLEY, G.D. (1994). Spontaneous bigeneric hybrids in Cactaceae. Bradleya 12: 2-7.

Illustrations

Pachypodium 'Arid Lands', a wonderful creation from Chuck Hanson of Arid Lands Nursery in Arizona. P. succulentum (left) and P. namaqutanum (right) are the parents.

Fig. 1 Cremnosedum 'Little Gem', an intergeneric hybrid of Cremnophila nutans and Sedum humifusum

Fig. 2 Disocactus X mallisonii, a wide cross long favoured as a basket plant for conservatories

Fig. 3 Fruit in vertical section (x 4) of Disocactus X mallisonii showing a few plump seeds, It is 15 mm in diameter

Fig. 4 X Pachyveria pachyphytoides, a vigorous hybrid descended from Pachyphytum bracteosum X Echeveria gibbiflora Metallica'

Fig. 5 Another Pachyphytum bracteosum hybrid: X Pachyveria sobrina. The other parent is an unrecorded species of Echeveria

Fig. 6 Aloe jucunda (left), Gasteria batesiana (right) and the first generation hybrid between them, a handsome but unnamed X Gasteraloe.

Fig. 7 Another X Gasteraloe dating from 1896: X Gasteraloe lapaixii between its parents Gasteria bicolor (left) and Aloe aristata (right).

Fig. 8 X Hoodiapelia (Luckhoffia) beukmannii, a naturally occurring bigener attributed to Hoodia X Stapelia parentage.

Fig. 9 X Dinterops 'Stones Throw', Steven Hammer's cross of Dinteranthus vanzijlii X Lithops lesliei.

Fig. 10 Results of Gil Tegelberg's remarkable mating of Pilosocereus palmeri and Disocactus speciosus.

Fig. 11 Ferobergia 'Gil Tegelberg'. Crossing Leuchtenbergia principis with Ferocactus cylindraceus has lost some chlorophyll on the way.

Fig. 12 Inflorescences of Gasteria (top), Haworthia (bottom) and a hybrid between them, X Gasterhaworthia bayfieldii.

Fig. 13 X Gasterhaworthia bayfieldii as illustrated by Salm Dyck in 1842, with the same sterile clone in cultivation today.

Fig. 14 A rare successful cross of Aloe X Haworthia: X Alworthia. The Aloe parent was A. bellatula, the Haworthia is unrecorded.

Fig. 15 A bit of everything inherited from Echinocereus knippelianus and Sclerocactus (Toumeya) papyracanthus. The flowers are all stillborn.

Fig. 16 Cleistocactus strausii X Echinocereus (Wilcoxia) poselgeri: another unexpectedly wide cross for the lover of oddities.

Fig. 17 Graptopetalum (Tacitus) bellum X Sedum suaveolens, a new X Graptosedum.